You are in: Home page > Magazine Archive > Water and the City

Philip Stessens, Annabelle Blin

Water and the City

Unintentional Urbanism

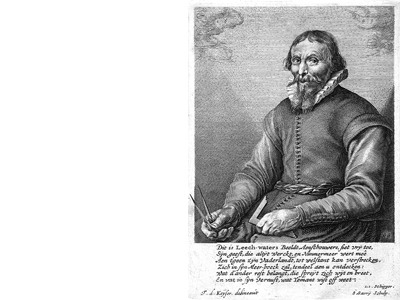

Gravure of Leeghwater, 1654

Water and Bordeaux

Water has played an important role during the city-state’s construction. Since Roman time, Bordeaux has been a flourishing town and port with connections particularly with Spain and Britain (“Encyclopædia Britannica,” 2014). Jumping ahead in time, by the 17th century, numerous Bordeaux vineyards were already operational, but much of the region was still unusable swampland. Under the direction of the Dutch hydraulic engineer Jan Adriaanszoon Leeghwater (1575-1650) (Figure 1) wetlands on the left bank were drained, leading to easier transportation of people and goods, and an increase of farm land, now home to many of the currently successful vineyards. Several of the channels and dikes are still in existence. Further up the Garonne near the center of Bordeaux, boats were berthed at the harbor, and smaller barges loaded with food products went up the tributary rivers through the city (Figure 4, Figure 5). From either side of each beck, warehouses are located, piers are constructed, and there is one wooden bridge after the other, connecting the two banks. An architectural and infrastructural vocabulary is thus created from the hydrological features of the territory.

From 1830 until 1890, the City of Bordeaux grew to an impressive 250% of its original population and was even more densely populated than today1 (Figure 2). In the later part of the 19th century we witness the birth of modern urban planning, reacting to public health issues in the overcrowded industrial city. At that moment urban planning was considered mainly as an answer to a human health crisis2. Avenues were constructed speculatively and tributary rivers evolved into an extensive open sewer. Riverbeds were subjected to some shrinkage and transformed into channels. In the metropolitan region of Bordeaux (la CUB), the amount impervious surface kept growing, with a steep rise parallel to the automotive industry.

Urban planning was less driven by the natural conditions, leading to deep changes of the original landscape. Now just parts of the rivers are visible, most of those weak water pipes are underneath the roads, diverted, and submitted at the land pressure. Today, we see a new tipping point, as we see being reflected in the AIA 'Decade of Design' mission statement: “Interestingly, health becomes again a driver for urban planning and design. But the current approach of sustainable development in the context of climate change and biodiversity stress is different and more complex. Planners can not solve this challenging situation alone, it requires interdisciplinary collaboration”3 .

Epiphenomenistics

The water-related consequences of continuous urban development are starting to show clearly in cities around the world. Firstly, local problems such as storm flooding and the Urban Heat Island (UHI) become more apparent, which are both directly linked to an increase of impervious surface, simultaneously, small open streams reduce in volume due to the lower ground water recharge (Batelaan, De Smedt, & Triest, 2003). Secondly, climate change, driven by non-sustainable urban development, aggravates these problems. These changes imply a great stress on most existing ecosystems (Wilby, Perry, 2006) and will change our environment fundamentally. When we observe the behavior of the city under climate change scenarios, we can see that in some Western-European climate urban heat wave events in cities tend to be double in 2071–2100 in comparison to 1961–1990, while the increase remains small in rural areas (Hamdi, Van de Vyver, De Troch, & Termonia, 2013). This is threat for life expectancy (Gabriel & Endlicher, 2011), making the UHI an important problem to tackle. Health concerns are once again a driver of planning: “the way we layout cities, does affect our sense of well being, but also our physical health” (Yvy, CEO of the AIA, 2013).

Masson et al. (2013) studied the numerical modeling of the Parisian UHI and its remediation and concluded: “This induces a 'reversal of our point of view'. Up to the end of the 20th century, cities were designed mainly through their main driver: infrastructure. Now, most of the infrastructure is in place and the city planning approach of this early 21st century is seeking to harness a new driving force, sustainable development. We are now turning our attention to the geographic and natural aspects, inside and outside the city, and to the living environment. Working on the city-climate combination leads to a new way of designing the city.” The questions of urban change and transformation must be met on a different footing straddling both nature and culture (Pickett, Cadenasso, & McGrath, 2013), and a better understanding of the impact of (re)development on environmental quality is based on interdisciplinary collaboration. As Pickett et al. (2013) write in the introduction of their book on resilience and design: “all of these changes […] produce unprecedented complexities that demand solutions that go beyond the empirically familiar and disciplinarily comfortable. […] What new theory might emerge to accommodate such novelty? How can that theory advance the practice of ecological urban design?”

Even when the field of ecology is reduced purely to the ecosystem services4 it delivers, the interaction of heat, water and vegetation is highly complex. On the other hand, developments in simulation techniques of the last two decades are starting to broaden our understanding. However, it is absolutely crucial for these algorithms to be coupled with the field of design.

Design and modeling

If the way of thinking cities could be reversed by first using geographical, climatological, topographic data as a methodological leverage, city planning would have another shape and new typologies of architecture would be revealed.

Researchers are now bridging the gap between geography and urban design, by creating GIS5 models that inform planners, policy makers and (landscape) urbanists with simple spatial indicators. Where exactly does the creation of green spaces have the most flooding or climatological impact? How do water regulations influence the ground water table and hence the evapotranspiration6 cooling capacity of trees during hot summer days? Where does the population have a lack of which type of green spaces? What is the actual effect of removing a barrier or connecting green spaces? What is an environmentally suited place to build or to densify? These GIS models can monitor the environment through time, but also allow scenario impact testing. We can ask ourselves whether the knowledge these models bring, will become visible in the city’s structure. Will, in time, the city show its topographical, climatic and hydrological sensitivity?

There are, however, two crucial aspects to this story. Firstly, models are always an approximation of reality. The key is to accept them as such, and to make them skillful, to make them give us new insights (TED, 2014). Moreover, there is a danger that models put us on the wrong path. Interpretation and linking results to other perspectives is therefore one of the new tasks of the designer. Secondly, projection is different from prediction. There is still a need for designers to project their vision and to communicate clear projects. An example is the vision for Bordeaux7 in the framework of «55 000 ha pour la Nature», more specifically the valorization of the «jalles»8. Through a thorough and intensive reading of the (urban) landscape, a very powerful «Exemplary Landscape» is shown (Figure 6). The specificity of this approach lies in bringing forward an intention by simply filtering the existing situation. This allows a very clear communication to all of the stakeholders involved.

Steps forward

In 2010, La CUB launched a project to envision 50 000 new housing units around public transport nodes, and in 2012 it launched «55 000 ha pour la Nature», in which five interdisciplinary teams were asked to ¬present a global vision and then to work on one specific theme, such as «the valorisation of floodable and wet zones» or «reinforcing the green and blue network». It is the first time in France, that the role of nature inside an agglomeration is conceived in such an integrated way, with its social, economic and environmental functions. Equally new is the fact that cities of a same metropolitan area engage in such intense collaboration for taking up common challenges, backed up by an interdisciplinary think tank, that includes landscape designers, planners, philosophers and specialists of agriculture, soils and forest management. Even though the evolved city has gained the capacity to overpower local landscape structures, the insight is returning that reinforcing their inherent qualities is a pathway to produce a new physical and social climate. We are at this point, however, still far from an overlap of the different fields of urbanism. For example, La CUB has missed the opportunity of creating strong ties between the two projects. As well in science, as in practice and governance, we can observe a real progress in understanding the city, including step by step a consciousness about «epiphenomena», there is a capacity to develop the tools and frameworks in a way we never thought architecture, urban planning and landscape in the same time, but it is still far from a mature practice.

[1] Source: until 1999: EHESS – Cassini villages in today’s administrative boundaries on the website of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales. From 2004 onwards: INSEE – Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques

[2] Other motives include the imposition of control and speculation

[3] The AIA 'Decade of Design' mission statement; this ten-year AIA pledge will document, envision, and implement solutions related to the design of the urban built environment in the interest of public health and effective use of natural, economic, and human resources.

[4] Since the last decennium of the 20th century, the concept of Ecosystem Services (ES) gained an important role in the debate on sustainability and quality of life (Lappé, 2009) (Burkhard, Petrosillo, & Costanza, 2010). Neßhöver et al. (2007, in (Bastian, Haase, & Grunewald, 2012)) consider ecosystem services as the missing link between ecosystems and human wellbeing. According to the Millenium Assessment Report (2005), ecosystem services can be defined as the benefits mankind receives from ecosystems.

[5] Geographic Information System, a digital system for geolocation and analysis.

[6] Evapotranspiration is a contraction of evaporation and transpiration. Transpiration by vegetation happens through the opening of leaf stoma and is directly dependent on the ground water level. When water is (evapo)transpirated, heat is extracted from the air by the phase transition from water to vapour.

[7] Project by Bureau Bas Smets (project leader) in collaboration with lAUC, Transsolar, Earth System Sciences from Vrije Universiteit Brussel, CAFSA, Campana Eleb Sablic, LAMS, NFU, Office KGDVS and Sebastien Marot.

[8] Tributary rivers to the Garonne, as earlier discribed.

Demographic evolution of the Commune de Bordeaux