You are in: Home page > Magazine Archive > Non-stop city

Born in the USA, perfectioned in Japan: a typical store of 7-Eleven’s competitor Lawson. Image source: Lawson, Inc.

Whoever zapped to MTV in October 2002, most probably came across the music video for Justin Timberlake’s first post-boyband single. The clip showed the singer dancing and flirting outside a 7-Eleven convenience store located on Virginia Beach’s Pacific Avenue. Surrounded by muscle cars, BMXs and loitering teenagers, the setting suggests a very American kind of suburban urbanity. To some 1, also the encounter with the convenience store chain must have been a premiere. But while the clip successfully depicts 7-Eleven as a site for social exchange, its outdated brick building labels it as a rather stodgy typology. A sort of well-equipped gas station without gasoline, posed randomly into the urban fabric wherever it offers enough space to accommodate an oversized front parking lot?

Quite the contrary: if Timberlake had cycled down Pacific Avenue a few hundred meters on one of the bikes featured in his video, this would have led him to just another 7-Eleven branch, followed at regular intervals by several others – iterating like the background image of early Disney cartoons. A view on a larger map reveals that the equation defining this pattern is derived from a business strategy that aims at area domination, ultimately minimising the distance between the store locations to a one-and-a-half mile radius for free-standing sites (like the one featured in the video clip). A gap reduced to only a quarter of a mile for urban walk-up stores 2. But in order to fully implement and refine itself on this second, smaller scale, 7-Eleven had first to turn the back to the American “Autostadt” in search of a suitable urban fabric elsewhere.

Ultimately Japan would prove itself being the fertile urban hotbed 7-Eleven was in need of. There, it installed itself in November 1973, opened its first store half a year later, launched 24-hour operations in 1975, attained already 1,000 stores at the end of 1979, acquired its meanwhile bankrupt American holding in 1991 and continued its steady growth which at present marks a total of 18,000 stores – one third of its global branches 3. Although in Japan 7-Eleven is the leader of its market segment, by operating virtually 1 convenience store out of 3, the franchisor has been rapidly flanked in its ascension by other chains such as Lawson, FamilyMart or Circle K Sunkus. Collectively they operate 55,000 stores (1 per 2,320 inhabitants), totalling 5% of Japan’s annual retail market sales 4..

In Japanese convenience stores are called “konbiniensusutoa”, shortened konbini, a loan-word transliterated and pronounced in the Japanese language syntax from the English “conveni(ence store)”. Their “Nipponization” and rapid expansion, has been favoured by the high number of public transport commuters, the early development of highly computerised logistics, the country’s low crime rate (a precondition for 24-hour opening times), but ultimately also its very specific urban fabric. In fact, even if Japanese cities are synonym for urbanisation, they are still able to offer less dense – hence calm and comfortable – moments. A typical city block in Tokyo is surrounded by tall apartment and office buildings, which conceal an intricate capillary network of small alleys flanked with detached houses.

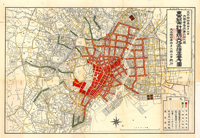

This hybrid condition is the result of fire prevention regulations, notably those introduced after the two mayor burnouts of Tokyo: the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 and the bombings of World War II. By learning from these disasters, the government designated the main streets as routes for evacuation in case of emergencies and the resulting border zones as commercial areas. By allowing an increase of the floor area ratios of these buildings, the resulting “pencil towers” form a sort of city wall, encircling the low-rise residential areas and preventing the extension of fire from one area to another. Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, co-founder of Atelier Bow-Wow, compares the morphology of these urban villages with “cream-filled pastry”, called shūkurūmu in Japanese – a transliteration derived from the French (pâte à) choux and the English cream.

This hybrid word describes two very different spatial qualities: a hard outer one (the chou) that is at once fast and characterised by inner city car traffic, and a soft inner one (the cream) featuring a slower and more human scale that has been amplified over time by the increasing subdivisions of private parcels 5. 7-Eleven approaches such a neighbourhood by “creating community-based stores that accommodate the characteristics of the trading area”. Through this contextualisation, the stores’ design and sizes (30–250 m²) 6 are determined and their flexible inventories adjusted to the neighbourhood’s demands. The fulfilment of a Metabolist’s dream, as the architects Hiromi Hosoya and Markus Schaefer argue: “They are subject to a strategy, not a form; a network, not an architecture; an algorithm, not an ideology. Their urban presence is pure process.” 7

This results in a highly “vitaminized” suburban urbanity, in which the Konbini’s seem to have contributed in levelling out the paradigm of collective and individual living. If über-compatibility was a premise for their installation, their contribution in formalising and consolidating these “creamy”, but still metropolitan, environments also acted as facilitator for a certain type of architecture. There’s rarely a day passing on which “architectural broadcasters” like ArchDaily or Dezeen aren’t greeting us with a new Japanese house8. And while we can explain ourselves the size, the location and extravagance of these projects based on historical and cultural grounds, the design of many would still be unimaginable elsewhere, where individualism and self-sufficiency still determine more hysterically the elements of suburban houses: garage, pool, garden, forecourt, etc.

Evidence for a mentality that learned to outsource certain “essentials” of individual living can be in fact found in some of the most known Japanese houses of the last decades. While Shigeru Ban’s Curtain Wall House (1995) still limited itself to address and merge the antagonisms of the private and the open, Ryue Nishizawa‘s Moriyama House (2005) already explodes the volumes that make up a “house”, while the House NA by Sou Fujimoto (2010) proceeds in dissolving interior and exterior spaces. Projects that have as a precondition that the city with its amenities is always in reach, always opened, always offering exactly what one is looking for. With their flexible inventory, 7-Eleven-like stores are a kind of pragmatic climax of omotenashi, a term at the core of Japanese hospitality, describing the anticipation of the guest’s needs by its host.

Besides food, Konbini’s offer ATM services, postal and delivery services, payment services (for utilities and taxes), ticket services, and recently also city services enabling customers to get residence certificates (juminhyo). By theoretically being exactly what one needs it to be – whether as tourist, inhabitant or worker of an area – the Konbini also anticipates the needs of the entire city, both on micro and meso scale. While places for casual social interactions like the German kiosk, the French boulangerie, the Italian bar or the Polish “milk bars” are limited to one function and restricted opening hours, the Konbini have the surplus of making “the metropolis” available 24-hour a day, at a few meters from each inhabitant’s doorstep. A peak of activity is possible anytime and anywhere, the metropolis always ready.

[1] Although 7-Eleven is the world's largest operator of

convenience stores, it is only present in 16 countries.

[2] Strategic Retail Management,

Zentes, Morschett, Schramm-Klein, 2nd edition 2011

[3] Annual Report 2014, Seven

& i Holdings Co.

[4] lawson.jp/en/about/business/

[5] A frequently necessary

maneuver for the successors of landowners, due to the high inheritance taxes

applied in Japan (up to 50%).

[6] Regulation, Distribution

Efficiency, and Retail Density, David Flath in Structural Impediments to Growth

in Japan, National Bureau of Economic Research (2003)

[7] Tokyo Metabolism, Hiromi

Hosoya, Markus Schaefer in The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, Rem Koolhaas

et al. (2001)

[8] Two Sou Fujimoto houses are

within the Top 10 of the Most Visited ArchDaily Projects of All Time. Its more

design-oriented counterpart Dezeen is even featuring an own archive of over

three hundreds such delights: #japanese-houses.