You are in: Home page > Magazine Archive > Changing Cities

Susan Dunne

Changing Cities

Dispersed Urbanism in an Irish Context

Abstract

This brief essay questions the use of traditional urban design methods in the dispersed city and seeks to explore new overlapping strategies to be used when regenerating or invigorating the low density urban environment. The article illustrates various student projects generated during the urban design workshop "Changing Cities" in Nantes School of Architecture (led by design tutor Susan Dunne) where the students explored three cities in Ireland (Belfast, Limerick and Tallaght).The three cities that have in common low density dispersed urban conditions that go hand in hand with a high concentration of socio-economic problems. An interdisciplinary flexible design approach forms the basis for the project proposals creating new situations and new energies as opposed to master planning a formal response.

Dispersed urbanism presupposes that urbanism has been dismantled and dispatched, hence destroyed, leaving behind something that is not urban; in the words of Bruce Robbins1 the phrase dispersed urbanism has “a calculated ambiguity”, he questions whether “a version of urbanism persists, however paradoxically, as urbanism somehow takes on a dispersed form?” (Robbins, 2008).

This raises the question of what is urban or what is an urban area and if it is dispersed, how do we (architects, designers, planners etc) classify and analyze the fabric that remains?

Urban areas are traditionally characterized by high density population cores and low density hinterlands, and follow a recognizable pattern. Urban areas may be cities, towns or conurbations; they develop following a process of urbanization and are commonly monitored by measuring the population density development. Traditionally urban design in historic urban cores deals with conventional forms (dense inner city formations, urban plazas, street-scapes etc.), and entails the identification, enhancement and intensification of these elements, which in turn often leads to reinstating and reinforcing the existing urban fabric.

Dispersed urbanism does not follow a characteristic pattern, it can take on a multitude of formal or informal spatial and social organizations, including urban sprawl, suburban development, inner city voiding out, makeshift shanty town etc. Dispersed urban settlements do not “suggest” any particular design approach (formal or programmatic) neither do they rely on conventional forms. New and variable design strategies have to be developed to deal with the looseness and the diverseness of the dispersed city, in the words of Ells Verbakel2, we may ask “Can the notion of the city be established through combined degrees of interaction, access and communication that do not necessarily require high density?” (Verbakel, 2008).

The question is how as designers do we approach the low density dispersed city, what skills or parameters do we draw on to revitalize an environment that at first appears to be an un-cohesive “méli – mélo” of non-descript ad-hoc developments. How do we manage the emptiness, the unpredictable and the sometimes damaged fabric (be it social or material) within these urban contexts?

The informal nature of the spatial and social structures in the dispersed city are not only to be found in the suburban low density or fringe developments but are visible in many city centers, where the voiding out of the city center has created a patchy city by day and a ghost town at night (notably when the inhabitants have deserted the center in favor of suburban dwellings and/or when shops, offices or complete building premises are left vacant following an economic crises).

Networks, both digital and physical (high speed transport infrastructure), have also fundamentally modified the morphology and sociology of public space and the urban environment – no longer do we consider the city just in terms of its center and periphery, we measure its vitality by its connections. Paul Virilio3 states clearly that “the architecture of systems has definitively replaced systematic architecture and urbanism” – he considers that transport intermodal hubs are replacing the “rooted urban experience” as speed and connections are becoming the predominant considerations in the increasingly mobile society we live in (Virilio, 1984).

Whether we agree that digital or high speed (transport) systems are taking over the public arena is one thing, but we can only agree that nebulous and multiform structures have largely replaced the traditional urban forms or models. To address urban dispersal we need to understand contemporary notions of public space, scale, diversity and flexibility. These are the particular characteristics that can serve to generate new innovative programs, polarities or new situations, yet we still tend to draw on traditional urban design ideologies such as density, commercial main streets, plazas or enforced pedestrian movement even when these notions are not necessarily applicable in the contemporary environment.

Changing Cities Studio workshop in an Irish context – Student Projects

The student projects illustrated hereafter are drawn from the architecture and urban design studio “Changing Cities”, (which is a bilingual (English/French) workshop in Nantes School of Architecture) and attempt to address through interdisciplinary workshops (architecture/urbanism, sociology, geography) some of the questions raised in the first part of this article.

The studio investigates the multi-layered socio-economic and geographic parameters or conditions that participate in shaping urban environments. The workshop also questions the role architects traditionally play in the built environment, where they are all too often relegated to the role of “building designer” and given little or no leeway to participate in decision making on an urban or territorial scale, contribute to establishing the program, or interface with the future users or neighboring communities.

During three years the students participating in the “Changing Cities” studio explored different urban environments in Ireland, confronting Belfast in Northern Ireland, Tallaght (a satellite town near to Dublin) and Limerick (a city in the south west). Although the geography and history of each of these cities are very different, they have in common low density dispersed urban conditions that go hand in hand with a high concentration of socio – economic problems; massive unemployment, widespread poverty, social housing ranking near 40%, poor community infrastructure, extremely isolated housing estates and widespread social segregation.

Belfast was the most extreme of the three sites studied, due to its troubled history. The city suffered (like many places in Northern Ireland) from long periods of political instability and open conflict resulting in numerous causalities and consequential drastic urban policies - during and following the troubles (1968 – 1998) the city was designed and evolved around fear, control and separation. Security forces built “the peacelines” to keep the catholic and protestant populations apart, patrolled and developed ‘interface areas’ (buffer zones), limited pedestrian areas, increased car use and road infrastructure and fenced off behind barbed wire many community services (schools, crèches, youth centers, libraries, police stations, shops etc). As a result, a lot of the city dwellers deserted the city center in favor of suburban developments, leaving behind a city torn apart by conflict, bad urban policy and an economic crisis. Over half of the city center is made up of vacant plots and empty premises, and the suburban developments sprawl indifferently towards the sea and mountains. The city of Belfast still bears all too openly the marks of its traumatic history.

“Urban trauma describes a condition where conflict has disrupted and damaged not only the physical environment and infrastructure of a city, but also the social and cultural networks. But how is this trauma to be understood in its aftermath, and in urban terms?”4 (Lahoud, 2010).

Each of the cities (Belfast, Tallaght and limerick) were researched by the students at a distance and on site, visited, mapped, photographed, drawn, written about, walked, biked and bused, talked about, read about, lived in, in as much as is possible within the term time. The social and physical fabric of the cities and surrounding areas were explored, following a number of themes (housing, education, transport, industry, agriculture, social services, landscape, waste and recycling, tourism and commerce). After the research, each group of students had to choose a site and write a project program embracing an architectural, urban/landscape and social strategy.

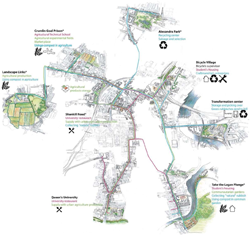

Though they are not physically connected the different project sites and programs overlap networks5, juxtapose diverse activities and create new intensities generating a new urban condition, fused by the different polarities. Landscape, agriculture, ecological tourism, and temporal programs are used to generate flexible design approaches. Mobility and access become the strategy for stitching back together the severed cultural and social fabric.

Project 1

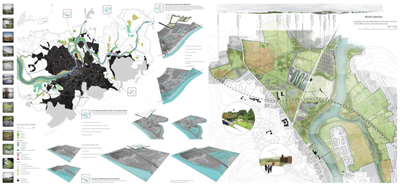

Limerick: From waste-lands to wetlands, ways to address the forgotten waterfront. (Project: F Hamon) (fig. 1-3)

Project 2

Belfast: New connections for a divided city (Project by: D Courroye, C Mougel, C Pederencino.) (fig. 2)

In Belfast the project proposals were developed overlapping complimentary programs ; the Lagan side “cultural quarter” project for residents, tourists and students interfaces closely with the ‘regenerated docklands’ project in conjunction with improving the boat, road and rail transport facilities. In the ‘ride to the other side’ project, the bicycle networks replace car lanes (to transport people, goods and waste), remodel urban infrastructure, promote social interaction, reduce environmental hazards and link the different project sites.The “Alexander Park” project hosts a new marathon event creating new trails through the park, the city and the outskirts linking the mountains, the city and the sea.

Project 3

Tallaght: Using road infrastructure to generate new programs (Project: F Bruneau) (fig. 4-5)

The innovative program and project morphology for the ‘data storage center and pedestrian link’ project at the Red-Cow cross roads were largely influenced by the distinct site characteristics – situated in the middle of a mega sized road infrastructure amidst very hostile environmental conditions (noise, pollution, wind , isolation etc).The site was chosen by the students (previous to writing the program) for its outsized dimensions and dramatic nature, the program attempts to weave diversity and humanity into what is considered a mono-functional road structure or non-habitable high speed connector.

Project 4

Limerick, Moyross : Regeneration through active participation (Project: C Cassouret, J Touchais, A Pinault) (fig. 6-7)

Flexible phased project re-development and community involvement form the backbone to the “Moyross regeneration” student project proposal. Moyross is a social housing estate on the fringe of the city of Limerick that was dismantled for economic and social reasons by the local authorities, dispersing many of the inhabitants (after having demolished their houses); the dismantling of the estate had disastrous effects on the people and the environment. The student project is an alternative approach involving training, participative refurbishment and phased regeneration. This student project was presented to the “remaining” Moyross inhabitants who engaged enthusiastically with the proposed process.

The projects described here have sought to uncover longer-term issues, pursuing social interaction, cultural and geographical connections, in doing so they propose new urban possibilities, a willingness to explore different approaches and an awareness and concern for the unique and individual situations within these urban contexts.

Note:

1 Bruce Robbins in his article "The Public and the V2" (AD magazine - Cities of Dispersal, Jan/Feb 2008) reviews Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity's Rainbow and questions the destruction and the dispersion of London City after the blitz during the Second World War.

2 Els Verbakel and Rafi Segal guest edited the AD magazine - Cities of Dispersal (Jan/Feb 2008), in their introduction "Urbanism without density" they question and review different forms of the dispersed city.

3 Paul Virilio (French urban planner and architect) published a dense philosophical text "L'espace critique" (in 1984) on Architecture in relation to "lost dimensions of space and technological transformations of time". The 1991 English translation "The Lost Dimension" is currently out of print.

4 Adrian Lahoud guest edited the AD magazine Post "Traumatic Urbanism" (Sept/Oct 2010); in his introduction he provides a critical framework for looking at trauma and the city.

5 The significance of employing overlapping strategies and networks has not been developed due to the constraints of this article, but the following quote sums up very well how in urban design it is desirable to build in forms of slack and redundancy as opposed to privileging “centralized efficiency” – “A resilient city is one that has evolved in an unstable environment and developed adaptations to deal with uncertainty. Typically these adaptations take the form of slack and redundancy in its networks. Diversity and distribution be they spatial, economic, social or infrastructural will be valued more highly than centralized efficiency”.

6 The reasons given by the local authorities for dismantling Moyross were both economic and social; the site was seen as an opportune site for a new modern suburban development (mixing different class structures and dwellings), the history of crime (shootings, muggings, drug abuse etc) in the area was considered sufficiently alarming to disperse the members of the community and dismantle two thirds of the houses. The subject of whether the dismantlement of Moyross was appropriate or not, cannot be treated here in greater depth due to the constraints of this article but it was one of the driving considerations taken into account by the students who proposed the Moyross regeneration project.

Bibliography

Choay F., (2006), Pour une anthropologie de l’espace, Editions du Seuil

Davis M., (2006), Planet of Slums, Verso

Friedman Y., (2011), Architecture with people, by the people, for the people, Actar

Lahoud A., (2010), Post traumatic Urbanism, AD September/October

Low S. M., (2011), Claiming Space for an Engaged Anthropology: Spatial Inequality and Social Exclusion, Article first published online: 24 aug 2011

Mongin O., (2005), La condition urbaine. La ville à l’heure de la mondialisation, Editions du Seuil

Robbins B., (2008), The Public and the V2, AD January/February

Sassen S., (2001), The global city: New York London Tokyo, Princeton University press

Segel R., and Verbakel E., (2008), Cities of Dispersal, AD January/February

Virilio P., (1984), L’espace Critique, Christian Bourgois Editeur

Susan Dunne is a practicing architect and design tutor, originally from Dublin. After receiving her degree from Trinity College Dublin she went to live and work in Paris, where she now has a design practice. She specializes in transport and Infrastructure projects, has designed the light rail stations for Roissy Charles de Gaulle Airport and the extension to Terminal 1 in Dublin Airport. She is currently designing three stations for the Rennes Metro (line B), refurbishing Rennes Airport and two Parisian metro stations. She leads a bilingual master course in urban and architectural design in Nantes School of Architecture and has taught in Paris, Rennes, Dublin and Belfast.