You are in: Home page > Magazine Archive > The temple and the universe.

Sandro Grispan

The temple and the universe.

When Le Corbusier received in 1945 the proposal by Edouard Trouin (1) to collaborate on the project of the Basilique de la Paix et du Pardon, dedicated to Mary Magdalene and to erect at the foot of La Sainte-Baume (2) in the south of France, he imagined a building 220 meters high, in the shape of a truncated cone, «hollow like a bell» (3).

But going up the mountain during a visit to this place characterized by the magnificence of nature, Le Corbusier abandoned his dream of constructing a building to surpass the peak in order to gain a view of the sea towards the south (4).

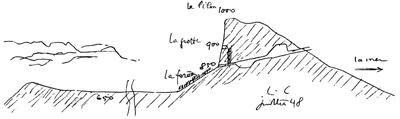

From the idea shared with Trouin of an architecture hidden «inside the rock», in 1948 Le Corbusier drawn a section of the basilica carved into the mountain, composed by a gallery along which two large spaces are placed, one turned downwards and the other turned upwards.

Flora Samuel suggested that the cryptic drawing of Le Corbusier can be interpretated as representation of a mandala, a model of the spiritual order of the world, with reference to La journée solaire de 24 heures drawn by Le Corbusier himself (5).

In fact, the similarity between the symbol and the architecture comes out not only comparing their respective shapes, but especially considering the intelligibility of their forms.

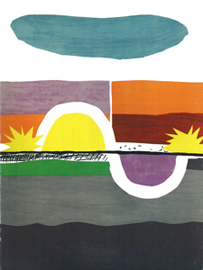

In the solar day of twenty-four hours, Le Corbusier represents his own vision of the world, of nature and man, of the correspondences between the Macrocosm and the Microcosm, through a cosmological archaic conception based on the cyclic structure of Time (6). This graphical representation basically consists of a straight horizontal line, the earth, and a sine wave that tracks the movement of the sun across the sky during the course of an entire day. Intersecting the sinusoid in the inflection point, the earth-line divides the movement-line of the sun in two parts, corresponding one to the day and the other to the night. For archaic man, the «earth» was in fact the plane passing through the ecliptic. More specifically, the «emerged earth» was the plane passing through the celestial equator. In this way the equator divided the Zodiac, disposed along the ecliptic, into two halves. The first of these two halves, namely the northern zodiac arch that extends from the spring equinox to the autumn equinox, passing through the summer solstice, was the «emerged earth»; The second one, namely the southern zodiac arch that extends from the autumn equinox to the spring equinox, passing through the winter solstice, was the «sea» (7).

But what helps us to better understand the common meanings between the twenty-four hours symbol and the section of the underground basilica at La Sainte-Baume is the interpretation made by Richard A. Moore of Le Poème de l'Angle Droit (8), the graphic and poetic work in which Le Corbusier expressed his cosmic and symbolic vision and of the world.

Let’s look the drawing placed at the center of the first level of the Poème’s iconostase (9) (A.3 milieu), the one in which the man Modulor is above the opus circulatorum, the alchemical circle, divided by a cross indicating the four cardinal points. The circle is broken at two openings located on an imaginary axis that connects the north and south. From an astronomical point of view (10) we can consider these two openings as the moments when, during the year, the sun stops to rise or fall in relation to the celestial equator, namely the summer solstice and winter solstice, which coincide with Cancer and Capricorn zodiac signs.

According to the relationship between the Zodiac and the «evolution of the soul through the worlds» of the Pythagorean cosmogony (11), the extreme points of the tropics of Cancer in the north and Capricorn in the south are the «gates of heaven», respectively the «gate of men», through which the soul falls on Earth, and the «gate of gods», through which the soul ascends to Heaven (12).

In the drawing of Le Corbusier, the Modulor man is placed over two red triangles which remind of the two pyramids that Le Corbusier himself reproduces in the series of paintings entitled Taureau, where the pyramid with the base facing the ground represents matter, and the other with the base facing the sky represents spirit (13). In the same way, the two triangles in the drawing of the Poème represent the dual nature of man, spiritual and material, made of body and soul. The man upright on its own feet, a symbol of life, is crossed by the horizontal line of the sea, a symbol of death, which marks the transition from the material to the spiritual dimension.

Then, let's look other two drawings of the Poème: the ones where the Capricorn, that so important mythological figure of the classic zodiacal conception of space and time, is painted (14). The drawings are those placed at the centre of the fourth level (D.3 fusion) and on the right of the third level (C.5 chair) of the iconostase.

In the upper part of the first drawing, the Capricorn has its head turned downwards and invades the lower part of the same drawing, where a woman and a man are coupled. The «violent act of communion» between the woman and the man refers to a symbolic variant of the alchemical fusion (15), the sexual metaphor of the Chemical Wedding between opposing principles, masculine animus and feminine soul. The Capricorn, above, symbolizes the elevation of the spirit freed from matter.

In the other drawing (C.5 chair), the image of Capricorn who hovers in flight with a smile takes us back to the doctrine which tells of the fall of souls on Earth, through the «gate of men», and their ascent on Heaven, through the «gate of the gods» (16).

The same that Homer represented with the description of the cave of Ithaca in the Odyssey (17), whose verses in the edition purchased by Le Corbusier in 1909 say: «La grotte a deux entrées: l’une tournée au septentrion, et ouverte aux humains; l’autre, qui regarde le midi, est sacrée, et leur est inaccessibile: c’est la route des immortels» (18).

During his research dedicated to the chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Haut in Ronchamp, Mogens Krustrup was convinced that the sacred cave described by Homer presented many points in common with Ronchamp. Krustrup interpreted the work of Le Corbusier as a cosmic model, believing that the south door of the chapel, which rotates on a pivot at its centre axis, indicates the axis of the two equinoxes when it is closed, and the axis of two solstices, Cancer and Capricorn, when it is open (19).

Moore, however, believes that Le Corbusier gave to each element of the chapel a specific orientation according to the four cardinal points and infers that the sharp corner that rises facing south evokes the horn of Capricorn drawn by Le Corbusier himself (20). We might add that with the highest tower facing north it reconfirms the solstice axis along which the evolution of the soul goes on, from its incarnation in the body until its freeing on Heaven.

But if La Sainte-Baume generated Ronchamp, as many authors have often said (21), is it perhaps possible that the forms, drawn by Le Corbusier, of the spaces of the Basilica of Peace and Forgiveness acquire a clear meaning through the symbolic, metaphysic and cosmologic interpretation of the relationship between man and the universe and are thus better understandable from the point of view of their architectural composition?

We don’t have to forget that we are at La Sainte-Baume, the Tabor of Mary Magdalene, the one who gave the world the example of the sublime triumph of spirit over matter.

The disposal of the interior spaces of the basilica carved into the mountain can therefore be considered as an initiatory path that aspires to reconcile man with the fate of his soul and to raise him to the dimension of the sacred placed within himself.

Imagine then to enter into the underground spaces drawn by Le Corbusier and join the rhythmic-sensorial experience with the imago mundi that the ever changeable concatenation of the shapes of emptiness seems reveal.

Crossing the entrance of the basilica on the northern slope of the mountain, we have behind the constellation of Cancer. In a symbolic way, we are going through the «gate of men».

After the first part of the underground gallery, we arrive in the first large space which represents, with its presumed shape of a truncated cone with the larger base facing upward with respect to the processional path, the moment when the soul dies, takes bodily form, or falls on Earth.

After the second part of the underground gallery, we enter into the Magdalene's Sancta Sanctorum which instead represents, with its presumed shape of a truncated cone, with the larger base facing downwards with respect to the processional path, the liberation of the soul from the body, its return to the divine, or its ascent to Heaven.

Finally, after the last part of the gallery carved into the rock, we go out on the gentle southern slope of the mountain, with our eyes turned toward the constellation of Capricorn. In a symbolic way, we are going through the «gate of gods».

And then, the elusive space beyond the horizontal line of the sea leads us to explore that inconceivable void where the perception of a sacred dimension lies: the depth of our self, the abyss where the Truth lives.

1. Edouard Trouin, surveyor of Marseille, met Le Corbusier in Paris April 1, 1945 and talks with him about plans of a sanctuary dedicated to Mary Magdalene, the Basilique de la Paix et du Pardon, and a new settlement, the Cité de contemplation, to build on the extensive grounds of his property at the foot of La Sainte-Baume.

2. La Sainte-Baume is one of the highest mountains of Provence, a huge rocky outcrop majestically overlooking a dark forest and containing the grotto where Mary Magdalene, according to the legend that tells of her arrival by boat on the southern coasts of ancient Gaul, she would have spent the last thirty years of her life in repentance and mystical ecstasy, until her ascent to Heaven.

3. Cf. E. Trouin, letter to Le Corbusier, Paris, 2 april 1945: «hollow like a bell» (eng. trans. by the author of the essay).

4. L. Montalte (Edouard Trouin pseudonym), Fallait-il bâtir le Mont-Saint-Michel?, Editions L’Amitié par le livre, Bainville 1979, pp. 97-100.

5. Cf. F. Samuel, Orphism in the work of Le Corbusier with particular reference to his unbuilt scheme for a basilica and city at La Sainte-Baume (1945-1959), a thesis submitted to Cardiff University for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor, MA Dip Arch (Cantab), The Welsh School of Architecture 2000, p. 189.

6. It seems that Le Corbusier wants to share and recreate that firm grip on the "conceivable" of the archaic man, that vision of the cosmos framed in a temporal and eschatological order which had sense for him and reserved a fate for his soul. Maybe it's the Timaeus of Plato, repeatedly cited by Matila C. Ghyca in Le Nombre d'Or, that revealed to Le Corbusier the reason that in early times it was mandatory observe with the greatest attention the immense cosmic clock. In the Platonic image of the world, the soul of man, when it is right, participates in both the harmony of the cosmos as the bliss of the gods; it is bound to Heaven from which it came, thus returning to its star, to live there and lead a life of happiness.

7. G. de Santillana – H. von Dechend, Il mulino di Amleto. Saggio sul mito e sulla struttura del tempo, Edizione Gli Adelphi, Milano 2007, p. 83.

8. Cf. R. A. Moore, Alchemical and Mythical Themes in the Poem of Right Angle 1947-1965, in «Opposition», 19-20, MIT Press 1980, p. 111.

9. Le Corbusier named iconostase the schema at the opening of the Poème made of seven layers, each of which corresponds to a specific theme and to a key color, that indicates the partition of the work. This configuration refers to the dividing structure adorned with sacred images interposed between the chancel and the nave of the ancient Byzantine basilicas. As well as the structure screened Eucharistic rites which only the priests and the initiated could assist and at the same time revealed to the faithful the promise of salvation, the iconostase of Le Corbusier is set up as a spiritual order and reveals the intention to consider the Poème as almost a religious text. Cf. R. A. Moore, Alchemical and Mythical Themes in the Poem of Right Angle 1947-1965, cit., p. 135.

10. Le Corbusier had an original edition dated 1880 of C. Flammarion, Astronomie Populaire, C. Marpon et E. Editeurs Flammarion, Paris, from which presumably derive the astrological themes that, with those alchemical and mythological, are contained not only in the Poème de l'Angle Droit, but also and especially in the painting, sculpture and architecture of the last years of his life.

11. Among the great initiates of the past, the one to whom Le Corbusier is particularly interested in is Pythagoras. As witness the many underlining and margin notes in Les Grands Initiés by Edouard Shuré and Le Nombre d'Or by M. C. Ghyka in its possession, the Pythagorean «numerology» is the most well-known subject by which he is attracted. Less well known is his likely interest addressed to the parallel concept of spiritual cosmogony or «evolution of the soul through the worlds», a doctrine that is known, apart from the Pythagorean initiation, under the name of the transmigration of souls. Cf. Edouard Shuré, I grandi Iniziati, Editori Laterza, Bari 2007, pp.304-305).

12. Cf. J. Carcopino, La Basilique pythagoricienne de la Porte Majeur, L’Artisanat du Livre, Paris 1926, pp. 368-369.

13. Cf. N. Jornod - J.-P. Jordod, Le Corbusier (Charles Edouard Jeanneret). Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, Skira Editore, Milano 2005, nota 1, p. 935.

14. It is not the first time that this mythical figure appears in the painting work of Le Corbusier. In September of 1948, Le Corbusier painted the mural of the Swiss Pavilion, where every form and shape refer to mythological and symbolic meanings associated with the processes of alchemical transmutation and sublimation of continuous separation and unification of opposites. The belief expressed by Richard A. Moore in Alchemical and Mythical Themes in the Poem of Right Angle 1947-1965 (Cf. pp. 117-118) that the mural was intended to be read from right to left, as the Zodiac, leads to recognize the winged female figure with a goat's head, on the right side of the painting, as the first of a long series of drawings of Capricorn made by Le Corbusier.

15. In the alchemical process, the term fusion means the moment when two principles are mixed to liberate the pure element (lapis philosoforum). The figures contained in the bottom of the design of Le Corbusier in fact, derived from the representation of the alchemical coniunctio sive coitus, the metaphor of spiritual liberation of consciousness.

16. René Guénon points out that it is not a theory more or less artificially constructed by the Pythagoreans or others, but rather a traditional knowledge found also among the Greeks before Pythagoras himself. Cf. R. Guénon, Il simbolismo dello Zodiaco nei pitagorici, in Simboli della Scienza sacra, Adelphi Edizioni, Milano 2006, p. 208.

17. How do reveal Porphyry (Porphyry, De Antro Nympharum, 22) and Macrobius (Macrobius, Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis, XII).

18. Homère, L’Odyssée, Editions Flammarion, Paris 1909, Chant XIII, p. 210: «The cave has two entrances: one turned to the north, and open to humans; the other, that looks to the south, is sacred and inaccessible to them: it is the road of immortal» (eng. trans. By the author of the essay).

19. Cf. M. Krustrup, Ronchamp, negli abissi abita la verità, in G. Gresleri, G Gresleri (a cura di), Le Corbusier, il programma liturgico, Bologna 2001, pp. 111-112.

20. Cfr. R. A. Moore, Alchemical and Mythical Themes in the Poem…, cit., p. 126.

21. Cfr. S. von Moos, Le Corbusier, l’architecte et son mythe, Editions Horizons de France, 1971, p. 124; J.-L. Herbert, La pensée religieuse de Le Corbusier, «Echanges», 180 (1984), p. 39; G. Gresleri, Le Corbusier sacro, «Arte cristiana», 712 (1986), pp. 57-62.

Sandro Grispan (Neuchâtel 1968) lecturer in Architectural Design at the

University of Parma, took his PhD in Architectural Composition at the IUAV University of Venice.

Le Corbusier, Le Poème de l’Angle Droit, 1955. Lithography chapter A.1 milieu. FLC Rés C 62