You are in: Home page > Magazine Archive > Broader than Broadway

Job Floris

Broader than Broadway

The anomalies within the grid

Observing the intriguing Flat Iron Building in New York, raises the question what conditions lead to the realisation of this exceptional triangular structure. The Fuller building, as the original name goes, was completed in 1902 and designed by the architecture firm led by Daniel Burnham. The triangular shape of the building was caused by the intersection of 5th ave. and Broadway, a historic road and the big exception in the rigid grid of the Commissioners' plan. For one, the economic climate must have built up such pressure on the available land, that it eventually led to raising buildings on off-standard plots. Secondly, the urban plan was demanding and firm in maintaining the perimeter of this triangular plot, at the expense of conventional architectural conditions. This comprised into high inefficiency on the ratio floor versus elevations, simultaneously to the sheer beauty of an unconventional volume. A precursor is the Times building at Times Square, designed by Eidlitz & McKenzie in 1903. Unfortunately it was killed softly due to various reconversions. This grand tower house was genuinely celebrating the escape of the narrow footprint into vertical directions by far. Forming a hybrid of a monumental cathedral and an office building showed consciousness of both the designers and commissioners of the potentials of the plot. While the Flat Iron Building is probably the most well known example, with Broadway as exemplary for an exception in a grid, this transcends New York. Situations of an urbanism overruling architecture by creating extraordinary building-types, is to be found in other places as well, such as Paris and Rome among others. This phenomenon appears in several densified cities throughout the world, although the reasons behind differ. This gives rise to the exploration of exceptions or flaws in the logic of urban plans. Caused by observations of unconventional typologies of thin, shallow and wedge-shaped buildings emerging as a consequence of the meeting of an implemented urban plan into an existing city-fabric.

In Paris, this phenomenon seems to be more complex, consisting of several forms. Here, the implementation of the Haussmann-plan between 1853 and 1870, created a plurality of wedge-shaped buildings. The star-grid caused triangular building blocks on purpose: this was planned instead of a flaw. The overall parallel is formed by an architecture that was subordinate to the rules of urbanism1. And eventually, this longing for a new, modern urban image led to a richly varied amount of housing typologies. Besides, there are situations where the old and the new structures were having a rendezvous, which culminated in the form of the towering wedges. These are moments were the explanation of the new avenues had to proceed to the extreme, in spite of practical issues. As a result, these buildings seem to form an independent typological category, neither solely belonging to the scale of architecture, nor the one of urbanism. The attraction is in the autonomy of these objects: they behave as unhinged parts of a bigger block. Cleary a member of the family, as the facades completely blend in, almost camouflaging their unusualness. But, their proportions stand out as they are vertically elaborated, forming an ambiguity between a bloated house and a reduced urban block. Nevertheless, they form an indispensable part of an urban gesture, while challenging architecture to simultaneously form filling mastic and obey to the urban representation.

Apart from the phenomena in Paris, in general it is hard to interpret these urban anomalies as conscious, deliberate parts of an urban strategy. Nevertheless, these collisions are causing fascinating urban moments, where the merge of urbanism and architecture might be at its best. The anomalies can be perceived both as a strange object and the ultimate obedience to the urban plan. By following the rules of urbanism to the extreme, buildings with exotic qualities arise, of importance as indispensable pieces of enforcement of the urban pattern. On contrary, seen from the architectural perspective evokes several questions. Such as, do these anomalies in the urban morphology cause an architecture that is completely subservient, and being manipulated into an inconvenient position of the non-optimal, inefficient and highly expensive appearances by the force of Urbanism? These leftover pieces are totally off-standard, causing difficult ground figure plans. Caused by ignorance, or does urbanism consciously challenges architects to be exotic, to obey and simultaneously offer broader interpretations of programs and rituals of use and inhabitation? Simultaneously, the ground plans also offer distinctive apartments of one whole floor, where the conventional habits of residents will be challenged. Having windows all around, intrinsically the daylight will flood the apartment. Although the triangular ground figure plan belongs to the in-crowd of hard-edge suckers for elementary and radical geometric forms, contemporary architects hardly succeeded to realise such buildings with confidence and conviction, while the historical Paris suffers from abundance. Of course completely not in pace with contemporary economics but how sharper the angle, the better it gets as the buildings starts to act like a thinning slab – up to point zero. This causes all kinds of interesting problems, like the ratio between the serving and served spaces. The historical layout of the Parisian apartment perfectly suited this odd shape, as the ensuite principle with long enfilades, eliminated the corridor: one was led through the rooms instead. The core being automatically directed to the deepest part of the plan, causing difficult room plans, for people desiring rectangular spaces in life. A striking example of a triangular tower, designed without any urban plan requiring such form, is the one of J.J.P. Oud in The Hague, The Netherlands. As part of a large congress centre, the tower formed a beacon and was realised in 1969. Apart from being abandoned and no program to fit in nowadays, which emphasises the unconventional shape, its equal triangular plan causes the beautiful effect of a thin sheet hanging in the air. This deludes the eye, as the depth of the building is only to be observed by a serious peek around the corner, where one usually meets the next elevation in a comforting angle of ninety degrees.

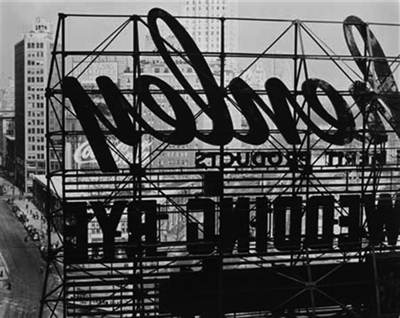

Besides triangles, in general: let us consider these anomaly buildings both as pivotal actors within the urban strategy and as exotic anomalies. As omitting would cause an undesirable big exception that would weaken the urban fabric. Their role compares to a breeching block. Therefore their elevations have to blend in, according to the formal rules of the street. Simultaneously, the conditions of the plot are intrinsically difficult. The exotic is encrypted in the shallowness of plots that offer space for merely a thick façade. It bears in mind the idea of a Potemkin-village. A cardboard building, a huge publicity sign, or a Decorated shed. Since the performance of the elevations and the floor plans is detached; they are both building up different narratives, which offer unlimited and challenging opportunities for architects.

[1] As described in “Urban Forms: The Death and Life of the Urban Block” Jean Castex, P.Panerai. Ivor Samuels. Routledge 2004