You are in: Home page > Magazine Archive > Enamouring Images

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, fresco of Good Government, detail (1338-39). Siena Palazzo Pubblico, Sala dei Nove.

Abstract

Impossible research in architecture, or the impossible as research. The impossible with all its load of temptations and hopes has been assumed in this article as energy, revitalizing the meanings that promote a good birth for an architectural project. This is the impossible making of images that are capable of reflecting the logical and symbolic dimension of the forms of architecture, mutually boosting them. Impossible research to be reduced to a mere discursive reason for the production of meanings generated by the IT/media world, but necessary to reawaken the constitutive interweaving of an imaginative conception of the architectural project, and constitutive of the soul of reality.

ROMEO: "It is my soul that calls upon my name / How silver-sweet sound lovers' tongues by night, / Like softest music to attending ears! In the garden of the Capuleti house, Romeo and Juliet are gripped by the sincere vortex of thoughts and actions in which imagination invents fantasies and images of freedom. Here the virtuous imagination, the most vital "instrument of the soul", combined within the senses and desires, enamours. Perhaps this same support and nourishment, a good, sincere imagination, is what architectural design needs. In fact, architectural design is the imagining and arranging of things so as to promote events. JULIET: "Conceit, more rich in matter than in words, / Brags of his substance, not of ornament. / They are but beggars than can count their worth. / But my true is grown to such excess / I cannot sum up sum of half wealth."

From the words of Romeo and Juliet, what is offered for our consideration is that the stream of consciousness of the poetry with its imaginary events, as too the conception of a project or the realization of a work, seem to blossom like fruits from the pathos of the soul rather than develop as a proof of discursive or productive reason itself. The words of Shakespeare are asking our consciousness to awaken to grasp and interpret reality so that our every action, our every project, are not devoid of meaning and trapped in functional attachments and instrumental deviations.

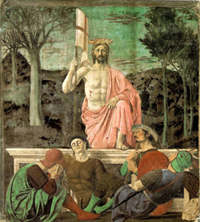

On the Risen Christ by Piero della Francesca in Sansepolcro, Massimo Cacciari wrote that: "the term 'sacrifice' is absolutely misleading; here it is the pureness of giving oneself, in its most conscious and free measure free, since here the gift does not correspond to any calculation, is not in view of any effect. This act of giving is im-possible for the human soul, because of its invincible philopsychia. However, never has the Word been preached with more force than by this silent lonely figure. It opens up, through its sheer presence, to the idea of the im-possible for us, that is to say, the extreme possibility that arises, that gives itself the capacity to match the extent of freedom, knowledge and giving, which in Him, for a single time, is embodied." (1) These words clarify the meaning of the fresco by Piero della Francesca in which the 'fragile dignity' of man is called upon to be reflected in expectation of the im-possible event. In this fragment, and even more so in the entire text by Cacciari on the Risen Christ of Sansepolcro, the words are born and enchant proceeding from a mute image. It is from this visual image that the event of the discourse begins; the start of a search for its meaning and symbolism. A discourse that becomes powerful and impressive, precisely because it develops by inextricably articulating relationships between thought, language and image. If, in fact, we tried to 'listen to' the resurrection only through discursive language, thereby progressively distancing ourselves from the visual image of the Risen Lord, from the elements of visual pathos, to develop more and more the traits of an explanation of the theological, or some abstract meaning of the resurrection, there would be an increasingly greater risk of forgetting the Risen One himself, his pathema, his face. This distancing determines our unconscious detachment from the 'interfering' world of Life, from the figure of life lived, and from what cannot be understood of it fully, in the direction of discursive, reassuring explicit truths, and the incontrovertible images towards which the worlds of science or mass media information tend, for example. The experimental and linguistic power that scientific and IT/media logic bestow on the will of man consist precisely in being able to describe, explain, and predict, with more and more correspondence to the things and facts they refer to, what is and what can become worthy of interest and of the greatest profit for man.

Now it is clear that architecture, as a worthy product and instrument of the lives of men, cannot avoid tackling research and interrogation into what it is, into what it should be and how to achieve these interrogations. Thus, observe the essential differences between the image of Sansepolcro; we can say that the risk of annihilation of the pathetic element and the figure of life lived that it is possible to detect when the human need for knowledge moves progressively in favour of the triumph of the discursive and abstract element, as in the example of the distancing from the conceptual meaning of the Risen Christ from its visual image can also be perceived for images that are not sacred in the strict sense. And within the limits that every architectural image sets on the search for sense of a vision that is prefigurative and transformative of reality, the same discourse can be adopted in the reading of architectural project images and research.

The way of expression in search of the im-possible truth is also that which Manfredo Tafuri has suggested contemporary architects follow, inviting them to revive the relationship between thought and image by drawing from the voices and works of genius of Humanism and the Renaissance. This invitation, certainly not without risks and not easy to follow, is combined with advice to take the Renaissance's energy and original power, freeing oneself from the deceptive idea that sees the time of rebirth exclusively as the initial point, the origin of an extended process solely "on an inclined plane, Teleologically oriented towards the triumph of contemporary calculating and scheming thought". (2)

The need for a rediscovery of the languages and forms of Humanism, the Italian Renaissance and of the "semantic vertigo on which it rests" was also the subject of reflections by the philosopher Roberto Esposito. This semantic vertigo veers in the direction of an "impossibility, for the human being, to be defined affirmatively as such, and therefore the need to be qualified in relation to that which, being more and more, or less of Man, decentralizes him driving him beyond himself". (3)

In his Labirinto Filosofico, Massimo Cacciari returned to emphasizing the opportunity of revitalising the relationships between the thought and basic image of the very heart of the Western soul, and to reaffirm that thinking in images "constitutes the profound trait of Humanistic thought, and, I would say, the characteristic, if there is one, of the genus italicum of philosophizing". (4) The words which Massimo Cacciari invites us to listen to, in order to reactivate the vital energy peculiar to the philosophical and artistic languages of the Renaissance, are drawn from the arguments of Plato's Philebus: "Wise images the philosopher wants to paint in the soul (Philebus) and make it love them."

The philosopher, according to Plato, and the humanist, artist or architect of the Renaissance paint images through their specific languages following the clues of the authors cited. That is to say, they do not only carry out exact logical reasoning. Their thinking and doing, their words and their forms are imaginative, i.e. they produce and stir up images in the soul of men, which can make them fall in love. Imagination, as a fundamental faculty of our soul with which we produce images, according to Plato/Cacciari, is not merely a faculty with which we enter into a relationship with the sensible aspect of reality. It produces forms in our consciousness. The meaning of this imaginative gait "a sort of thinking in images, or thinking imagery" (5) constitutes, also according to Roberto Esposito, the way in which the world came to light for Humanism. In fact, he wrote: "The whole of Humanism [ ] replaces the creative power of verba by the substantial entity of res, the inventive acuteness of' ingenium by the metaphysical fixity of essentiae, the contagious plasticity of imaginatio by the abstract rigidity of logic". (6)

Therefore, the medium with which our consciousness, our interiority, works in order to relate to external reality is of an imaginative, fantastic order. The shifting relationship of our consciousness with the world takes place through the production of images and forms. Therefore, given that we are in an imaginative relationship with reality, thinking in pictures appears constitutive of our being here.

If we follow this productive energy and the clues that Cacciari's text provides, we can recognize that, like every other moment of our consciousness, so also does project research develop from our being here, making an image of it. This means that an image is immediacy and mediation, a real or hypothetical reflection of a life-giving original reality able to demolish the composed uniformity of things, bestowing on the real the search for the impossible. The image is therefore a constitutive element of communication; of language, it represents the silent, mute, hence truly original part. But no language and no image ever exhaust their meaning. There is always something of an idea that language fails to express, just as there is always something of an image that remains indefinable. In this unexpressed, or in this invisibility that is present in our experience, the intimate passions and the inventions of men are enclosed and live. "The image does not 'repeat' the idea, to be used, perhaps, by the memory, but in-dicates what the idea alone cannot represent. And this is true for a quite essential aspect, that is still difficult to comprehend, due to the dualistic-esoteric misunderstandings that 'offend' Renaissance Neoplatonism: speculation (speculum) never reaches its end without contemplation (a 'figure' of the future visio facialis), but this is not such if it does not bring pleasure. Pleasure means touching the subject of one's own philia, or one's own eros." (7) The image, as the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy wrote, is constitutively absenso, i.e. "something that gives its truth only in portraying its presence". (8) A lack that enamours and that, therefore, is also pathos. No discursive thought and no kind of imagining can therefore be authentically such if we believe we can exclude the pathetic element from its expression. In this absence that becomes a presence, that becomes language and image, dwells the expression of sentiment. Thinking in images therefore implies the relationship that every language, whether verbal, visual, musical or even scientific, entertains with pathos, with sentiment. Expressing the sentiment of a figure is possible by putting it in an image. And the strength of the image, of the imaginative narrative element possessed by certain images, by certain works of architecture, enamours. But it is only through the image, according to Cacciari, that we "foresee" such joy. The first joy, bright and immanent of the pleasure born from contemplation.

The impossible search in architecture is a communicative intention. And it is also an exhortation to regenerate the links between thought and images. and the latter with the pathos they inspire. The awareness that the logos, the rationality that the architectural project must necessarily feed on, can communicate only if, internally, it likewise feeds the dimension overflowing with meanings flowing from emotion, passions and sentiments. In other words: the search for the relationships between thought/language/image/pathos is a search to be revived since it can restore a unitary vision of our being here as well as our making images, projects and works of architecture, without cancelling the complexity of the particulars that make up reality. Up to the deepest level that the search for the impossible may indicate. Up to the silence of the image that endows and enamours. Up to the search for the supreme good.

Reckoner / You cant take it with you / Dancing for your pleasure/ You are not to blame for / Bittersweet distractor / Dare not speak its name / Dedicated to all you all human beings / Because we separate like / Ripples on a blank shore / Because we separate like / Ripples on a blank shore / Reckoner / Take me with you / Dedicated to all you all human beings / Reckoner. Every occasion brings architecture to the threshold of a relationship with the other, with other disciplines, other hopes and expectations. In the architecture of the different sounds, rhythms and acoustic melodies of Reckoner by Radiohead, and in the almost unintelligible images that the voice of Thom Yorke evokes, lies an incommunicable, yet at the same time rational experience, which can only remain so enigmatic and has to do with its own truth, conceivably at the limits of the im-possible.

(1) Massimo Cacciari, Il Risorto di Sansepolcro, in Id. Tre Icone, Adelphi, Milan 2007, page 41.

(2) Manfredo Tafuri, Venezia e il Rinascimento, Einaudi, Turin 1985, p. XIX.

(3) Roberto Esposito, Pensiero Vivente. Origine e Attualitΰ della Filosofia Italiana, Einaudi, Turin, 2010, page 37.

(4) Massimo Cacciari, Labirinto Filosofico, Adelphi, Milan, page 132.

(5) Roberto Esposito, Pensiero Vivente. Op. cit., page 87.

(6) Roberto Esposito, Pensiero Vivente. Op. cit., page 41.

(7) Massimo Cacciari, Labirinto Filosofico, Adelphi, Milan, page 134.

Ildebrando Clemente is Researcher in Urban and Architectural Composition at the Department of Architecture of the Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna and PhD in Architectural Composition at the IUAV University of Venice.

The Risen Christ by Piero della Francesca. Fresco in the Palazzo del Governo city of Sansepolcro (1467-68).