You are in: Home page > Magazine Archive > Matter and Space

Gilda Giancipoli

Matter and Space

Compositional Theory in the Work of Oswald Mathias Ungers

Abstract

Between the multifarious theoretical studies and experimentations done by Oswald Mathias Ungers, in more than fifty years of his work, comes out one of the first compositional theory applied to the house-subject: the theory of “matter and space”, which introduces a hierarchic view of domestic spaces, also to reduce as much as possible distributive surfaces and to give more space to collective rooms of the house.

Article

To the extensive work of the German architect Oswald Mathias Ungers (Kaisersesch, 1926 - Cologne, 2007), took part also numerous theoretical insights and composition experiments, comprising the educational basis for his design evolution, culminating in the 80s and 90s.

After a debut in respect of modernists canons and a brief interest in the New German Expressionism, he, driven by the search for an autonomous compositional thought, made a personal reasoning on the perception of space, independent of contemporary architectural trends.

The theory of matter and space, which leaves traces in all his work, is one of the first theoretical elaborations of Ungers, comes out in the initial period of activity in Cologne, in the 50s and 60s, although the architect enunciated it only in 1963, when he wants to leave his expressionist past.

It is based on a purely philosophical consideration and, in fact, also physical: the observation of a constructive body is conditioned by the presence of a space in which it can be taken into consideration, vice versa, the perception of a space as empty, but having a shape and size, is subjected to its physical delimitation, through full and opaque elements: bodies.

As claimed by the city planner Fritz Schumacher, in his book Die Sprache der Kunst, which is considered the first written source for Ungers to develop this theme: «[...] refers to the awareness that, putting the mold of the mass, the goal of forming convex, plastics works, has pursued a completely different purpose, namely the formation of concave closed works: that is to say spaces [1]».Then we can outline that a concentric structure of the existing, in which the unlimited space freely contains the architecture such as housing of the interior space, enclosed and finished, that is the environment of human life, which is the center of this Ptolemaic figuration.

In the practical field, if one considers the dwelling, it consists of individual environments, with different distributional and dimensional characteristics in relation to the more or less characteristic collectivity of the rooms.

Ungers decided, therefore, to divide spaces into two categories: the bodies (matters) and spaces, or positives and negatives, determinants and determined, according to a reverse point of view, why what is negative and determined, the space, is more important than the "instrumental elements" which define it.

In this regard, at the Conference of Appointment Prinzipien der Raumgestaltung [2], at the Technische Universität in Berlin, 1963, Ungers declared: «In more general meaning, the architecture is nothing but the demarcation of visible air space from the smaller cell to the more complicated spatial construction».

The formation of the space (Raumgestaltung) through the formation of matters (Körpergestaltung) in association with the statement made by another source of Ungers: Hermann Sörgel with his Einführung in die Architektur-Ästhetik [3].

In pursuing this goal, Ungers conceives compartments according to simple and recognizable geometric shapes even through differentiation in the design plan. The formal fallout is expected that these compositional elements are not merely juxtaposed or arranged in line, but partially overlapping and intersecting. Consequently, the positive forms (opaque, filled) retain their formal integrity, while the negative ones, suffer the insertion of the constructive bodies, losing their figurative identity.

As even Reinhard Gieselmann initially guessed (Münster, 1925 - Karlsruhe, 2013), a friend of Ungers, architect and critic, this system is also a gimmick that allows the reduction of the area used for distribution to the rooms, allowing a seamless transition between the environments. In these terms, he, along with a group of young architects of Basel, had proposed to the CIAM in Aix-en-Provence in 1953, some arguments strongly influenced by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright on the house-subject.

For them, the ideal dwelling is the grouping of private spaces around a common central core, the living room, which brings together the family and at the same time serves as a hallway, around which all other housing functions have place.

The development of this theory by Ungers passes through the theoretical deepening, to which numerous architectural and philosophical contributions helped, including that of the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy, who in his Von material zu architektur [4] theorizes about the perception of space through movement, or the reading of the writings of Paul Fechter, as Die Tragödie der Architektur [5],where the architecture is seen as «active contrast to the space».

The practical application of this theory, it is definitely noticeable in 5 projects, between 1957 and 1967: the semi-detached house in Werthmannstraße 19, Köln-Lindenthal, 1957; House Bensberg, 1960 (never built); House Bauer in Overath, 1960-'61; the project for the district Neue Stadt, Köln-Chorweiler / Seeberg, 1961-'65 and the residential complex of the Märkisches Viertel, in Berlin in 1962-'67.

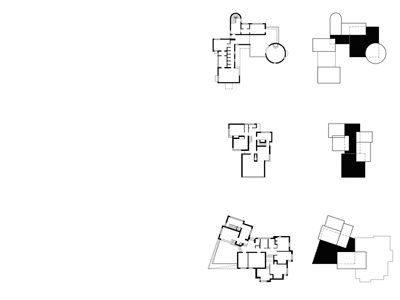

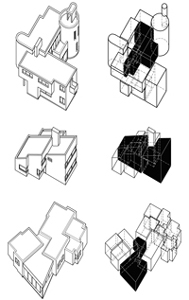

The case of Villa Müller in Werthmannstraße 19, as well as being almost certainly the first real application of the theory of composition of matter and space, it is also the clearest system: the geometric elements are few and easily recognizable. The rooms of the house are arranged into a "L" plant, to which is possible to enter from the intersection of the two sides. Uses are clearly separated: the north-south oriented segment is, on both levels, the sleeping area, and the east-west side the living area. In the latter area is recognizable an wide square living room, intersected by three positive elements: the cylinder of the library on the outermost summit, the diagonally opposite rectangle for service room and kitchen and, next to that, the stairwell leading to the higher plan, the ends of which semi-cylindrical externally emerge. The distinction between these few elements is enhanced by Ungers, conceptually and visually, in the design, giving the living room a fully glazed surface and a corporeality almost completely closed to the items placed on its diagonal.

The project for the house in Bensberg, which has just a hint of this theory, adopts a more enclosed and simplified system where the living room, always square, is no longer central, but is concerned by the inclusion of the fireplace and the intersection with the kitchen, while to a space of central hallway, almost symmetrical, adhere to the most private and service rooms.

The complexity of the plant increases considerably with the construction of the house Bauer in Overath. The project consists in two building blocks, called "Wohnhaus" and "Schlafhaus" [6] ("house for living" and the “house to sleep"), associated to the large rhomboid hall-living. Despite the composition heterogeneity, the system is clear: the positive elements are developed according to two distinct directionality, not perpendicular. To emphasize the character of reception and connectivity of the living room, this compartment is placed at a lower altitude than the rest of the house. In this project, it will provide a glazed surface on the two outer sides, which stands out sharply compared to the masonry volumes, covered with clinker, of the house. The strong integration with the positive volumes, makes it very difficult to guess the membership of the entrance hall to the negative connective figure, while the hierarchical importance of large positive parallelepiped central to the composition, consisting of the study and the master bedroom is such that prevail over other positive elements.

The example, in which the definition of the theory of matter and space reaches full expression, is the winning design in the competition for the district Neue Stadt, which defines a variant aggregation pattern, based on the form of the residence. To highlight even more this system, the positive matters are almost all made of a single room of rectangular or square shape and clearly separated, there is no contact between them. The transition between two positive rooms can occur only through the negative gap of the living room, except for services, such as bathroom and kitchen, often merged into one massive element. The result from the outside is a multiform set "towers", vertical, autonomous and continuous throughout the height of the building. Among the winning project and its effective implementation, there is much difference. Inevitably, the meeting between typological study and reality, determines the regularization of the compositional principle, making it less obvious the application of the theory of matter and space.

Similarly, this theory is continued by the residences designed soon after, the Märkisches Viertel district of Berlin. Accommodations are aggregated in groups of three to five, around a common stairwell. This organizational structure, unlike the previous Neue Stadt, relies on symmetry, organizing services in a sort of central positive cross-shaped form that defines the space of each apartment, while the private bedrooms, thought as bodies, occupy the vertices outside. The grouped structure, introduced here, is infinitely extensible.

In each of these cases, the theoretical principle of separation between the first finite elements and intersected spaces is generally respected and Ungers focuses on always confering to the negative spaces a glass surface in its entire width, so that also in the design in plant, this difference is understandable.

Subsequently, as a result of strong controversy received due to the high population density of the neighborhood Märkisches Viertel, Ungers will start a process of reconsideration of their convictions, looking for more stringent and simple forms. The interpenetrating compositional system of matter and space, as set out in his first creative phase, loses the formalism of intersecting geometries, giving way to pure independent volumes.

Notes

1 Fritz Schumacher, Die Sprache der Kunst, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart/Berlin 1942, p. 227.

2 Oswald Mathias Ungers, Berufungsvortrag, zu den Prinzipien der Raumgestaltung gehalten an der TU Berlin 1963, in “Arch +”, n. 181/182, december 2006, p. 43.

3 Hermann Sörgel, Einführung in die Architektur-Ästhetik. Prolegomena zu einer Theorie der Baukunst, Piloty & Loehle, München, 1918, p. 149.

4 Lázló Moholy-Nagy, Von material zu architektur, “Bauhausbücher”, Albert Langen Verlag, München 1929

5 Paul Fechter, Die Tragödie der Architektur, Erich Lichtenstein, Weimar 1922, p. 7.

6 O. M. Ungers 1951-1985. Bauten und Projekte, Vieweg, Brauschweig/Wiesbaden 1985, p. 65.

References

Sörgel, H. (1918). Einführung in die Architektur-Ästhetik. Prolegomena zu einer Theorie der Baukunst. München: Piloty & Loehle.

Fechter, P. (1922). Die Tragödie der Architektur. Weimar: Erich Lichtenstein.

Moholy-Nagy, Lázló (1929). Von material zu architektur, “Bauhausbücher”. München, Albert Langen Verlag.

Schumacher, F. (1942). Die Sprache der Kunst. Stuttgart/Berlin: Deutsche Verlagsanstalt.

Werkstattbericht, E. Bauten und Projekten von O.M. Ungers, in “Bauwelt”, n. 8, 51 a., 22 febbraio 1960 , pp. 204-217.

Ungers, O. M., Sozialer Wohnungsbau 1953-1966, in “Baumeister”, n. 5, 64 a., maggio 1967, pp. 557-572.

Ungers O. M., Zum Projekt Neue Stadt in Köln, in “Werk”, n. 7, luglio 1963, pp. 281-284.

Klotz, H., (1977). Architektur in der Bundesrepublik, Gespräche mit Günter Behnisch, Wolfgang Döring, Helmut Hentrich, Hans Kammerer, Frei Otto, Oswald M. Ungers. Frankfurt/M: Verlag Ullstein GmbH.

(1985). O. M. Ungers 1951-1985. Bauten und Projekte. Brauschweig/Wiesbaden: Vieweg.

Kieren, M. (1997). Oswald Mathias Ungers. Bologna: Zanichelli.

Neumeyer, F. (1998). Oswald Mathias Ungers, Opera completa. 1951-1990. Milano: Electa.

Ungers, O. M. Berufungsvortrag, zu den Prinzipien der Raumgestaltung gehalten an der TU Berlin 1963, in “Arch +”, n. 181/182, dicembre 2006, pp. 30-44.

Cepl, J. (2007). Eine Intellektuelle Biographie. Köln, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter König.

Gilda Giancipoli joined the “Aldo Rossi”’ Architecture Faculty of Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna in 2005. Author of the assay Ornamento e delitto, un film di Aldo Rossi, Gianni Braghieri, e Franco Raggi, in OMU/AR, CLUEB in 2010. Architecture graduate in 2011, with the subject “Sustainable Technology for Architecture”.She joined the Architecture PhD at the Architecture Department of Bologna University in 2012, ended it in 2015 with a research entitled: Oswald Mathias Ungers. Belvederestraße 60. Zu einer neuen Architectur.From 2015 she is Journal Manager of the Architecture Department of Bologna University’s e-journal In_Bo.