You are in: Home page > Magazine Archive > Notes on the carachter in buildings

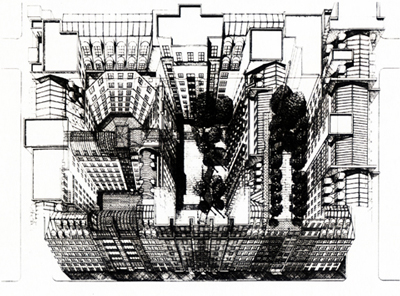

Aldo Rossi, Block in Schützenstrasse, Berlino, 1992, inclined table perspective (in Aldo Rossi. Disegni 1990-1997, edited by Marco Brandolisio, Giovanni da Pozzo, Massimo Scheurer, Michele Tadini).

Abstract

While drawing, architects leave their hands become part of that collective movement which during history proceeds in defining forms. From single constructions like the block build by Aldo Rossi at Schützenstrasse in Berlino in 1992, or drawing close rational architectures designed and realized in the same place, such as the case of Naples here examinated, mabe it is possible to argue that researching the character means reserarch the identity of the object, architecture and city, which the architects investigates.

Article

«Putting character in a work means using in the right way all the most suitable instruments in don’t leave us feeling other sensations apart of the ones characteristic of the subject itself», wrote Etienne Louise Boullée in Architecture. Essai sur l’art [1]. The sense of such a statement maybe is to be found in a conception of architecture which concentrates each effort of its own in maintaining itself close to the theme of the project investigated, or if you prefer to the object of project, as years ago said Giorgio Grassi in the opening lesson of the Academic Year at Milan’s Polytechnic [2]. Doing an example useful in order to keep clear the speech, and nevertheless without it implicates trespassing in another discipline with whom architects use to flavor their speeches, we remind to the sense of a far Tzvetan Todorov’s text, La quête du récit, that is The research of the tale, in which while talking about medieval romance on the search for Holy Graal he affirmed, like Italo Calvino reports, the reminding each other of the meaning levels of the tale without pursuits thrown towards the outside, just noting «the search for Graal is not other than the search for the tale [3]».

What just affirmed here it will be developed with other quotations yet, but after all with an example of architecture particularly full of meaning, trying then to refer about some our studies directed to develop this question that could be defined of «research of architecture», in other words a reminding each other of the elements on the play which has as its source the architecture, the building, the construction and nothing else, convinced as we are that positions sustained in the disciplinary field are to be measured through projects, starting from one’s own and despite all the limits and the lacks they can contain.

In order to summon a master at least similar to Boullée, Mies van der Rohe, we can quote the final lines of the text with which he introduces the small book condensing its work: «I believe architecture has less or nothing to do with the research for “interesting” forms or with personal inclinations. The true architecture is always objective, and it is expression of the intimate structure of the age in the context of which it works out itself [4]». About this passage Carlos Martì Aris develops some very useful observations, among which the one more suitable in the speech here played is the following: «What Mies refuses is […] the idea of “character” of building, based on an arbitrary and indiscriminated use of signs, to which is attributed the property of “communicating” what the work wants to be [5]». We suppose it is possible to recognize in transparence the consonance of the concept expressed by Martì Aris with the opposition to formalism always implied such as in the work of author of constructions such as in theorethical work of Giorgio Grassi, thesis supervisor for the Catalan architect in the doctorate of which Le variazioni dell’identità is the result. And moreover we will find again very similar concepts when Grassi himself will expose them in his lesson mentioned at the beginning.

If, as the architect of Milan writes, «The building’s character stands in its history, is written in the long process of definition which has leaded to the form which appears every time as it would be the first time, but instead, as we know well, is only its last incarnation, let’s say so, the more authoritative the more loyal to itself [6]», here it would be investigated on one side to what extent it is possible to push this notion in the compositional practice without falling down into formalism, and on the other, as it has been mentioned above, showing it by means of a concrete case study.

Trying to make it even more explicit than they already are Grassi’s words by referring ourselves, trying to keep them together, to the two levels of res aedificatoria wich refer to each other of the house and the city, and whereas Alberti himself underlined how «city is like a big house, and the house on its turn is like a little city [7]», well, it could be said this, that the work of the architect is to find the identity of the specific theme on which it is working. At the scale of the building that commitment consists in a research that involves on the one hand the question of the type in its progressive liberation from historical forms that shaped him, and at the scale of the city in being able to make intelligible those rational plots that define its warp. The liberation of the architectural type from its historical conditionings, that search of its adequacy on which linger as long Grassi in the lesson cited as for instance architect as Antonio Monestiroli [8], proceeds with the issue of integration of the building in one place making it adhere to the particular conditions that determine it, in the sense of the character of the building contained in the history of the buildings about which Grassi told. Just this compositional margin we would like to investigate the closer to show how to the building constructs the place according to the rules of the architecture and the city as the history of the forms that constitute them both.

Given the textual references cited examples perhaps would be natural to expect examples in the ranks of formal conciseness even not of the proper take off of the voice of the same Giorgio Grassi or the formal goals which Mies van der Rohe was able to reach. However, it is possible to use a different example, and that is that building for residences and offices built in Schützenstrasse in Berlin by Aldo Rossi now more than twenty years ago, in 1992 [9].

Building, this, quite far from mimesis with historical Berlin and maybe from some recent wills of making tabula rasa of the fourty years in which the choices about urban construction of half of the German capital depended by DDR’s socialist government. A clue is provided by Rossi himself – of whom it must not be left out the contribute in the knowledge of idea on architecture and city by Hans Schmidt, Swiss architect who in the DDR worked long time – when in rebuilding this block uses the insertion of two pieces, one a part of the preexisting block and the other the quotation of Palazzo Farnese, as to say the local condition kept intact on the one side and on the other tht more general condition, the model which assumes the connotation of the example. Besides all this, traits of the façade of different aspect and and yet held together thanks to the regulating plan which orders the correspondances according not explicit alignments. Rossi itself describes the compositional technique used for this building, dwelling upon an «idea of designing by using different quotations in different ways», which he observes already present in Berlin architecture’s masters such as Schinkel or Schlüter, noting then that it has been wanted to recreate the inner life of the block withut repeating what has been missed, and after all of having wanted «to offer alternatives to common building practice, with a variety of typologies rather than forms [1]0».

A similar technique is not too far from the one an author studied in depth by Rossi during his youth, Emil Kaufmann, defined of the «patterns with multiple correspondances [11]», and referring to the examples of the project for public baths by Alexandre Gisors of the house in rue des Fontaines by Loison. Individual buildings if confronted to this in Berlin which is a block, but the point in common it seems to us they have is their being constituted through a compositional technique according which, by using Kaufmann’s words, «the motifs composing the scheme respond one another becoming so “themes”. Several subcharts can then come into the talk by meaning of a remarkable differentiation in spaces, in dimensions or through games of numeric proportions [12]». Neither it needs to be underlined the importance of the research made up by French revolutionary architects to get architecture rid of the burden of redundancies and overabundances of form of the Baroque Age that came before it.

Although from last Rossi’s work a diffused common sense among architects inclined to keep distance, marking it as a post-Modernist conversion, it would appear an exercise not lacking in some result the one of arranging on single tables, city by city, all Rossi’s projects, and examining which urban idea it would result. Maybe it would be quite different from the Nineteen century’s one, and more aimed, for the single way of its own voice of architect, to the construction of a polycentric city, or open [13].

This the direction of a study developed by the author of the current text some year ago, where he attempted, even with the intention of catching the sense of compositions like that of the Città analoga by Rossi, rewriting it with his hands and of course not too far from having suffered its charm, of gathering on a same plan in a territorial scale of Naples rational architectures put down here during the time, less it didn’t matter a lot if built or even only thought. There had been gathered toghether different facts going from the great social architectures by Ferdinando Fuga, to Palazzo Reale, to the Mostra d’Oltremare, to the urban design by Luigi Cosenza in the post World War II period who shaped the form of a big city, especially for what concerned the redraw of the side towards the sea on Marina Street in front of the port, that in the meanwhile, as Italy lost the war, became a naval base for the Navy of United States, until the projects by Salvatore Bisogni for some quarters and parts of the city, to the projects by Rossi for Molo San Vincenzo and for an underground path between Chiatamone Street and Plebiscito Square, among the cavities of urban subsoil. Not a Napoli analoga on its turn, as instead a research aimed in letting come out a rational plan through those projects that light up it, and start from them as urban landscape and so formal world inherited from which draw materials.

This the direction too of another study drove to the building scale, under Professor Bisogni guidance, imagining to put it as a part of his general project for public and collective buildings and for the «clods» in which are gathered some of them for the territory of the hinterland north of Naples [14]. Theme was the one of an intercommunal civic building, in which, that is, politic and administrative personnel of more neighbouring commons would have faced those questione, from traffic, to urban planning, to commerce, in a better way resolvable into a general pattern compared with an expanding territory on its way of thickening, being overcoming the phase of urban sprawl. Architectural example in the research of Modern movement was the Palace of Justice in Chandigarh by Le Corbusier, while more far in time, but contemporary according to the idea of architecture we support, was the religious complex of San Peter in Aram in Naples, studied in the early Seventies by Agostino Renna [15]. The result of this study is so a building made by several different constructions linked up both from a plot of apertures and voids, both of metric and proportional correspondances, whose variety and whose character are not the point of start but the point of arrive working with finite number of materials extracted by architecture and city.

Notes

1 Etienne Louis Boullée, Architecture. Essai sur l’art, manuscript conserved in the National Bibliotheque of Paris (MS. 9153) with the drawings. Transcription by Helen Rosenau in H. R. Boullée Treatise on Architecture, Tiranti, London 1953, trans. in italian Architettura. Saggio sull’arte, with an introduction by Aldo Rossi, Marsilio, Venezia 1967, p. 74.

2 Giorgio Grassi, Il carattere degli edifici, lesson kept in occasion of the inauguration of the Academic Year 2003-2004, December 4th, 2003 at the Facoltà di Architettura civile of the Politecnico di Milano, in «Casabella», n. 722, maggio 2004.

3 Tzvetan Todorov, La quête du récit, in «Critique», n. 262, marzo 1969, citato in Italo Calvino, La letteratura come proiezione del desiderio, in Una pietra sopra. Discorsi di letteratura e società, Einaudi, Torino 1980, ora in Id., Saggi, a cura di Mario Barenghi, tomo primo, Mondadori, Milano 1995, 20013 p. 249.

4 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, introductive text without title to Mies van der Rohe. Die Kunst der Struktur, edited by Werner Blaser, Verlag für Architektur Artemis, Zürich 1965, trad. It. Mies van der Rohe, Zanichelli, Bologna 1977, 19912, p. 8.

5 Carlos Martì Aris, Le variazioni dell’identità, with a Premessa by Giorgio Grassi, Clup, Milano 1990, CittàStudiEdizioni 1993, p. 140.

6 Giorgio Grassi, Il carattere, cit., p. 12.

7 Leon Battista Alberti, De re aedificatoria, translation in Italian L’architettura, Il Polifilo, Milano 1966, transl. by Giovanni Orlandi, introduction and notes by Paolo Portoghesi, p. 64.

8 Gyorgy Lukács, Estetica, Einaudi, Torino 1960, p. 1210, citato in Antonio Monestiroli, La metopa e il triglifo. Nove lezioni di architettura, Laterza, Roma-Bari 2002, p. 24.

9 See Aldo Rossi. Tutte le opere, edited by Alberto Ferlenga, Electa, Milano 1999, pp. 402-407, and Aldo Rossi. Disegni 1990-1997, edited by Marco Brandolisio; Giovanni da Pozzo, Massimo Scheurer, Michele Tadini, with a text by Paolo Portoghesi, Motta Architettura, Milano 1999, pp. 90-97.

10 Aldo Rossi. Tutte le opere, cit., p. 402.

11 Emil Kaufmann, Architecture in the Age of Reason. Baroque and Post-Baroque in England, Italy, and France, Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1955, trans. in Italian L’architettura dell’Illuminismo, Einaudi, Torino 1966, 1991.

12 Id., p. 235.

13 Antonio Monestiroli, L'architettura della realtà, Clup, Milano 1979; CittàStudi srl, Milano 1991; CittàStudi Edizioni s.r.l., Milano 1994; reprint of the third edtion of 1985, pp. 71-72.

14 See the work by Marco Zamprotta in Ricerche in architettura, La zolla nella dispersione delle aree metropolitane. Resoconti della ricerca Murst 2000: Funzione e figura delle architetture pubbliche e servizi per lo sviluppo sostenibile delle aree metropolitane: Firenze, Milano, Napoli, Mestre, edited by Salvatore Bisogni, with texts by Salvatore Bisogni, Guido Canella, Gian Luigi Maffei, Franco Purini (responsibles of each Research unities) et alii, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, Napoli 2011, pp. 221-222.

15 Napoli: prospettive per l’architettura del Centro Storico, edited by the research group directed by Agostino Renna made up by Italo Ferraro, Ludovico Fusco, Enzo Mendicino, Francesco Domenico Moccia, «Edilizia popolare», n. 111, 1973, pp. 103-130.

References

Alberti, L.B.. De re aedificatoria; trad. it. (1966) L'architettura. Milano: Il Polifilo.

Brandolisio, M.; da Pozzo G., Scheurer M., Tadini M. (a cura di) (1999). Aldo Rossi. Disegni 1990-1997. Milano: Motta Architettura.

Ferlenga, A. (a cura di) (1999). Aldo Rossi. Tutte le opere. Milano: Electa.

Boullée, Etienne Louis. Architecture. Essai sur l’art, manoscritto conservato alla Biblioteca nazionale di Parigi (MS. 9153) con i disegni. trascrizione di Helen Rosenau in H. R. Boullée Treatise on Architecture, Tiranti, London 1953, trad. it. (1967) Architettura. Saggio sull’arte, con introduzione di Aldo Rossi. Venezia: Marsilio.

Calvino, I. (1980). Una pietra sopra. Discorsi di letteratura e società. Torino: Einaudi.

Grassi G., Il carattere degli edifici, lezione tenuta in occasione dell’inaugurazione dell’Anno accademico 2003-2004, il 4 dicembre 2003 presso la Facoltà di Architettura civile del Politecnico di Milano, in «Casabella», n. 722, maggio 2004.

Kaufmann, E. (1955), Architecture in the Age of Reason. Baroque and Post-Baroque in England, Italy, and France. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; trad. it. 1966, 1991 L’architettura dell’Illuminismo, Torino: Einaudi.

Boesiger, W. (a cura di) (1965). Le Corbusier et son atelier rue de Sèvres 35. Vol. 7, Oeuvre complète 1957-1965. Zurich: Les Editions d’Architecture.

Lukács, Gyorgy, (1960). Estetica. Torino: Einaudi.

Carlos Martì Aris, Le variazioni dell’identità, con una Premessa di Giorgio Grassi, Clup, Milano 1990, CittàStudiEdizioni 1993.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, testo introduttivo senza titolo a Mies van der Rohe. Die Kunst der Struktur, a cura di Werner Blaser, Verlag für Architektur Artemis, Zürich 1965, trad. It. Mies van der Rohe, Zanichelli, Bologna 1977, 19912.

Monestiroli, Antonio, (1979). L'architettura della realtà. Milano: Clup.

Monestiroli, Antonio, (2002). La metopa e il triglifo. Nove lezioni di architettura. Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Napoli: prospettive per l’architettura del Centro Storico, a cura del gruppo di ricerca diretto da Agostino Renna e composto da Italo Ferraro, Ludovico Fusco, Enzo Mendicino, Francesco Domenico Moccia, «Edilizia popolare», n. 111, 1973.

Tzvetan Todorov, La quête du récit, in «Critique», n. 262, marzo 1969.

Ricerche in architettura, La zolla nella dispersione delle aree metropolitane. Resoconti della ricerca Murst 2000: Funzione e figura delle architetture pubbliche e servizi per lo sviluppo sostenibile delle aree metropolitane: Firenze, Milano, Napoli, Mestre, a cura di Salvatore Bisogni, con scritti di Salvatore Bisogni, Guido Canella, Gian Luigi Maffei, Franco Purini (responsabili delle singole Unità di ricerca) et alii, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, Napoli 2011.

Pierpaolo Gallucci graduates in Naples with a general plan in which he draws up together the rational architectures conceived for that city and sometimes built, since those by Ferdinando Fuga in XVIII century to the masterplan by Luigi Cosenza after WWII until the studies and the buildings by Salvatore Bisogni based on an idea of open city. Ph.D. in Architectural composition at Politecnico di Milano-Bovisa with an essay where he analyzes the work by Agostino Renna, projecting his research on architecture on the background of Italian culture between the Sixties and the Eighties. In the courses of Architectural compositions at Diarc in Naples where he collaborates and he is Adjunct professor, he interests in treatises and in the theme of residence.